In July 2019, Morgan Cooper was in a hospital bed when her gastroenterologist, psychiatrist, internist, a few nurses, and her mother marched into her room. She was 16, and for four years Morgan had been having stomach pains every time she ate. It had gotten worse in high school. The doctors had tested her for allergies and ulcerative colitis and gastroparesis. All negative.

She had recently been diagnosed with median arcuate ligament syndrome—MALS, a vascular condition—and she was set to be operated on by a surgeon in Atlanta. But first she needed to gain 25 pounds, which wasn’t going well. She was five foot seven, 98 pounds, and she was being fed through a tube placed in her stomach.

Cooper had lobbied for the tube after seeing other spoonies with it.

The spoonies were Cooper’s whole world. She had discovered them late in 2018, right after she set up a separate Instagram account dedicated to her medical struggles (@morgansfight, which is no longer active). She told me the account was for updating the family and friends who were always asking how she was doing. But a single tap on the MALS hashtag—or the one for any other illness—instantly revealed a world of chronic illness sufferers who track their many pains, tests, diagnoses, and doctors visits online.

These were the spoonies. They were mostly young women, and it seemed like there were thousands of them. (There aren’t strong spoonie stats available, but there are a ton of Facebook groups and pages—one with over 130,000 followers; nearly three million tagged Instagram posts; and videos garnering nearly 700 million views on TikTok. According to the CDC, six out of every ten Americans suffer from a chronic disease, with four in ten having two or more.)

Cooper created a YouTube channel, too. “I had one video just called ‘I’m Sick’ and the thumbnail was me crying,” she told me. “On Instagram, whenever I would post a picture of me looking sad, or with pills in my hand, or in a wheelchair, it would get like 2,000 likes.” Pictures of Cooper smiling would get about 100.

The spoonies made Cooper feel less alone, but the more time she spent online with them, the skinnier she got. In her journal, she’d written: I don’t know if I will live to see college. “It really felt true at the time,” she told me.

On that summer day in 2019, the doctors had come for her phone. Cooper’s medical team was having weekly meetings to discuss her care, and her mother had just sat in on one, so Cooper suspects that she brought it up. The only way to get better, they’d decided, was to cut Cooper off from the spoonies.

“I was lying in the hospital bed and my mom plucked my phone right out of my hands,” she told me. Cooper said she went “ballistic.” She remembered screaming and crying. “I told them, ‘You’re taking away my only source of friendship and the only people who get what’s going on with me.’”

The blogger Christine Miserandino, who has lupus, coined the term spoonie in a 2003 post called “The Spoon Theory.” A spoon, Miserandino explained, equates to a certain amount of energy. The Healthy have unlimited spoons. The Sick—the spoonies—only have a few. They might use one spoon to shower, two to get groceries, and four to go to work. They have to be strategic about how they spend their spoons.

Since then, the theory has ballooned into an illness kingdom filled with micro-celebrities offering discounts on supplements and tinctures; podcasts on dating as a spoonie; spoonie clubs on college campuses; a weekly magazine; and online stores with spoonie merch. In the past few years, spoonie-ism has dovetailed with the #MeToo movement and the ascendance of identity politics. The result is a worldview that is highly skeptical of so-called male-dominated power structures, and that insists on trusting the lived experience of individuals—especially those from groups that have historically been disbelieved. So what do spoonies need from you? “To believe; Be understanding; Be patient; To educate yourself; Show compassion; Don’t question.”

Spoonie illnesses include, but are not limited to, serious diseases like multiple sclerosis and Crohn's disease, but also harder-to-diagnose ones that manifest differently in different people: polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), endometriosis, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, dysautonomia, Guillain-Barré Syndrome, gastroparesis, and fibromyalgia. Another spoonie illness is myalgic encephalomyelitis—or chronic fatigue syndrome—which has now been linked to long Covid.

These illnesses are often “invisible”: To most people, spoonies may appear healthy and able-bodied, especially when they’re young. Many of the conditions affect women more frequently, and most are chronic illnesses that can be managed, but not cured. A diagnosis often lasts for a lifetime, while symptoms come, go, morph, and multiply.

Spoonies find community in having complicated conditions that are often hard to identify and difficult to treat. That’s why a lot of spoonies include a zebra emoji in their social media bios, borrowed from the old doctor’s adage: “When you hear hoof beats, look for horses, not zebras.” In other words: assume your patient has a more common illness, rather than a rare one.

The spoonie mantra might be: I am the zebra.

Although the term is relatively new, the spoonies fit into a long history of women having amorphous, hard-to-diagnose conditions. Since ancient times, women who were diagnosed under the general category of “hysteria” were prescribed treatments such as sex, hanging upside down, and the placement of leeches on the abdomen. Then, in the 19th century, the new field of psychoanalysis concluded that women with hysteria were not suffering from physical disorders, but mental ones. Whether the women’s inexplicable pain was a function of their brains or of their bodies—or of each other (see mass hysteria), or of the devil (see Salem, 1692)—has always been a fraught subject.

And then the internet arrived and created a 21st century version of Freud’s Vienna, in which everyone was always on the couch, perpetually the patient.

“The only way you can get legitimacy and care is if you have a diagnosis,” Dr. Mark Sullivan, a psychiatrist at the University of Washington Medical Center, told me. Dr. Sullivan was talking about the American healthcare system, but he was also gesturing toward the whole of contemporary society and our quest for other people’s eyeballs, for their likes and shares and acknowledgement. Spoonie-ism amounts to an endless search for a diagnosis—a campaign to be taken seriously, to be tended to, to be granted care and attention (or “awareness,” to use the spoonie term).

“Pain is telling you something, but it’s not always easy to know what it’s telling you,” said Kevin Boehnke, a researcher at the University of Michigan’s Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center.

Sophie Jacobson is a 22-year-old from Stamford, Connecticut who’s active on spoonie Instagram. “I was a medical mystery for about a year starting in 2019,” she tells me. Her current diagnoses include POTS (lightheadedness), gastroparesis (stomach pain), endometritis (inflammation of the uterus lining), and mast cell activation syndrome, or MCAS, which causes her body to have allergy-like reactions to—it seems—nothing at all. She also suspects that she has Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, characterized by overly flexible joints and easily bruised skin, but she’s waiting on a specialist to confirm that.

This past spring, Jacobson dropped out of the University of Maryland and moved home. Most days she wakes up nauseous and has to vape some medical-grade marijuana to work up an appetite. Around noon she eats breakfast, usually pretzels or eggs with toast. She spends a lot of time in bed or on the couch watching television—she loves cartoons—and at doctors appointments. She has a lot of those. When her symptoms flare up, she uses a wheelchair to get around. Her old passions—singing, acting, volunteering—have been eclipsed by a kaleidoscope of ailments.

“Someone asked me recently, ‘Who are you outside of being sick?’ and my jaw dropped,” Jacobson said. “I had absolutely no idea how to answer that question.”

Spoonies came up alongside Web2, graduating from the blogosphere to Tumblr to Reddit, then on to Facebook groups and YouTube channels and Instagram accounts, and now TikTok. A spoonie might post a somber video on Instagram about her pain, and then in a subsequent upbeat post, give a shoutout to International Wheelchair Day. Many posts are about spoonies’ personal struggles (”Today I got 40 trigger point injections, 30 of which were along the full length of my spine,” a caption might read), but often posts will be addressed to other spoonies. On Instagram, a “Chronic Illness Advocate” named Megan educates her audience about “medical gaslighting,” which she says might include being told by your doctor to lose weight. She also offers $40 off Avulux-brand light-blocking glasses for people with migraines.

In a TikTok video, a woman with over 30,000 followers offers advice on how to lie to your doctor. “If you have learned to eat salt and follow internet instructions and buy compression socks and squeeze your thighs before you stand up to not faint…and you would faint without those things, go into that appointment and tell them you faint.” Translation: You know your body best. And if twisting the facts (like saying you faint when you don’t) will get you what you want (a diagnosis, meds), then go for it. One commenter added, “I tell docs I'm adopted. They'll order every test under the sun”—because adoption means there may be no family history to help with diagnoses.

But it’s not just eyebrow-raising advice spreading around social media. In some cases, it’s the symptoms themselves.

Over the pandemic, neurologists across the globe noticed a sharp uptick in teen girls with tics, according to a report in the Wall Street Journal. Many at one clinic in Chicago were exhibiting the same tic: uncontrollably blurting out the word “beans.” It turned out the teens were taking after a popular British TikToker with over 15 million followers. The neurologist who discovered the “beans” thread, Dr. Caroline Olvera at Rush University Medical Center, declined to speak with me—because of “the negativity that can come from the TikTok community,” according to a university spokesperson.

Dr. Sullivan, the UW psychiatrist, hadn’t heard of spoonies. None of the experts I spoke to had. But he worried that the internet had unleashed “communities of grievance” that led patients to adopt “victim mentalities.” He told me, “The idea is: ‘You have to accept the fact that I’m disabled even if you can’t see it, because that doesn't invalidate my experience of disability.’”

Spoonies have developed their own language, too. If you’re fed through a feeding tube, you’re a “tubie.” POTS sufferers are “potsies.” Those with Lyme Disease, “lymies.” I have pored over hundreds of their accounts, and they seem to think of their pain as something to be combated—but also nurtured.

Paulina Assaf is a psychotherapist at the Pain Reprocessing Therapy Center in Beverly Hills, a practice with a 200-person waitlist. “A lot of chronic pain is due to neural pathways in the brain, as opposed to structural pathways in the body,“ she told me. Assaf said that if a patient comes in with five different symptoms affecting five different areas of the body, it’s more likely that the pain is “neuroplastic.” This means that yes, the patient is actually experiencing pain, but not due to an organic illness. The brain itself is firing off pain messages, a kind of false alarm.

Likewise, several spoonie illnesses might be thought of as what doctors sometimes call “functional disorders”—meaning there is no known physical cause or confirmatory set of medical tests. Cases in point: irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia.

“Functional disease is a real and chronic problem,” said Dr. Katie Kompoliti, a neurologist at Rush University Medical Center who was part of the team treating the influx of tic-ing teens. “It’s just not the one they think they have.”

The spoonie phenomenon feeds into a mass wave of anxiety that, Dr. Kompoliti said, was prevalent among the young people who came down with tics overnight. The tics were symptomatic of “a mass sociogenic illness,” she added. “That is, it’s generated by anxiety in most cases, or another comorbidity, and then propagated by the ease of TikTok.” Dr. Kompoliti says she no longer sees teens coming in with TikTok tics – but scrolling the platform, I notice a new trend taking over, with videos now chronicling users’ experiences with Dissociative Identity Disorder, ADHD, and autism.

Dr. Sullivan said it was a mistake to focus on whether pain is real or imagined. “The focus should be, ‘What can we do to make it better?’” he said. On that score, the cultural critic Freddie deBoer has put it this way: “What I would love to achieve is a society where people don't feel like they have to medicalize their pain in order for it to be taken seriously as pain.” He adds, “You don't have to tell me that you have fibromyalgia. You can just be tired, and I can have sympathy for you as a tired person.”

Therein lies the root of the problem.

As Marybeth Marshal, 27, of St. Petersburg, Florida, explained: “There’s some people who deep inside don’t want to get better.” Marshal knows the spoonie world well. She dropped out of Boston College in 2016 to focus full-time on healing from fibromyalgia, and then Ehlers-Danlos syndrome—a rare disorder that affects somewhere between 1 in 5,000 and 1 in 100,000 people, according to the NIH. Marshal told me that in the early years, she was desperate for a diagnosis so that her family and friends would take her seriously. “I felt like I had to prove to everyone that it was all physical, and that none of it was mental.”

But after she got the diagnosis, after finally being admitted to this community of fellow sufferers, she started scanning their posts. They were in hospital beds and crying. They made her feel like she'd never get better, ever. “You can get addicted to being sad, and sick, and the attention you receive,” Marshal told me. “The ‘misery loves company’ thing makes you sicker.”

Another reason for spoonies’ failure to improve may be “secondary gain,” Assaf said. “There might be something you're gaining by having this diagnosis, like that it’s keeping you from a job that you hate, or from responsibilities that you don’t want to do.”

Marshal, who said she can’t relate to complainers, admitted that she’s had trouble transitioning from her bed to a wheelchair to a shower chair to becoming fully operational again. During her recovery, she read a book about the mind-body connection and sleep hygiene, and she went on a mood-stabilizing medication. “Sometimes when I’m invited to a social event, I’ll have to think to myself, ‘Do I really feel sick, or do I just not want to go?”

Three weeks after the phone-snatching episode in her hospital room, Cooper—cut off from her fellow spoonies—was sent to an inpatient eating disorder clinic where she stayed for three months, and where they took her off the feeding tube. “I learned to start eating by mouth again, which hurt like hell because I hadn’t used my stomach muscles in months,” she said.

While she was at the clinic, she thought about the long, tortuous road that had led her there.

A month before the intervention, in June 2019, she got her gastrostomy-jejunostomy, or G-J, tube. It was attached to a metal pole with wheels on the bottom so she could walk around inside. If she felt like going out, she’d take a backpack with a pouch full of liquid nutrition. The G-J tube would pump the food into her body at a prescribed rate. “The spoonies were competitive about the rates,” Cooper remembered. “If you had a higher rate, we somehow thought you’d be nourished faster and you’d get better, which meant you weren’t really sick. I’d freak out when they upped the feeds.”

The tube was a drag. And she wasn’t gaining the weight she needed for the surgery. But it did accomplish something else. “Once I got that tube, everyone in public asked me what was wrong, and if I was okay,” Cooper said.

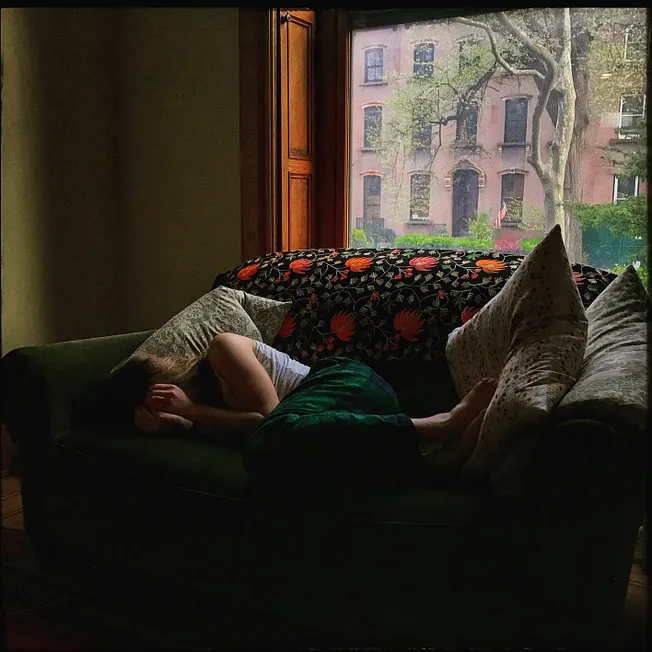

When she wasn’t in the hospital, Cooper would be curled up on her couch, chewing on ice and watching Grey’s Anatomy or YouTube videos of people eating huge amounts of food—up to 10,000 calories in one sitting. Mostly she’d swipe through her Instagram, spending hours responding to messages and seeking out other spoonies. Cooper’s account had 3,000 followers at its peak. She remembered looking at images from a more popular account with over 10,000 followers. “I was jealous of her,” she told me. “She looked so sick.”

Cooper coveted the other girl’s illness. “She had two tubes in her nose, and she’d post graphic medical updates and pictures of her body, and her pills,” Cooper said.

Cooper was jealous of the brand sponsorships, too. Her spoonie idol promoted salt tablets like vitassium, which can help with the lightheadedness brought on by POTS. Other spoonie products include a vegan leather pill pouch and probiotic-filled snack bars marketed under the slogan “Hot girls have IBS.”

When Cooper posted pictures of her own piles of pills, she’d pad them with over-the-counter supplements to make her condition seem more dire. This was known, in Spoonie Land, as “pill porn.”

She joined a group message on Snapchat called Sick Bitches. “All we did was message each other about negative things that were happening, like how our hips were hurting that day or if we had a headache,” Cooper said. She didn’t have a chance to tell the Sick Bitches where she was going before the doctors took her phone away.

She told me that when she finally got her phone back, “I got back on and thought, ‘Oh my gosh, was I a part of this?’”

Cooper was sitting in a Publix parking lot a few days later, taking in the Atlanta skyline with her mom, when she deleted her Instagram right then and there. “My mom was like, ‘Hell yeah!’”

In July 2020, Cooper finally got her surgery. It lasted five and half hours, and was intended to relieve the pressure on her celiac artery and to remove the bundles of nerves that cause MALS pain. She told me she still has some pain. “I could pursue more diagnoses, but at a certain point, what will that do?” she said. “I just don’t identify as a sick person anymore.”

In April 2021, she went to prom in a poofy red dress and red heels. That summer, she spent four weeks in Europe with her dad. “I loved the canals in Amsterdam,” she told me. She began riding a recumbent bike, going on long walks, and swimming in the lake by her family home. She enrolled in Piedmont University, in Demorest, Georgia, where she studies psychology. She hopes to become an art therapist in an eating disorder clinic.

But her spoonie self still lives in the back of her head.

“I’ll think, ‘Oh, life would be so much easier with a PICC line,’” she said, referring to a catheter used for long-term IV treatments. “I have to tell myself that it actually won’t make my life easier.”

Suzy’s most recent investigation was about the ongoing battle between Gibson’s Bakery and Oberlin College. You can read all of Suzy’s work here.

If you appreciate stories like this one, please become a subscriber today: